Winter Storm Fern has disrupted life for approximately 230 million people in the United States. C.S. Lewis and Oliver Burkeman have a few things to say about interruptions…

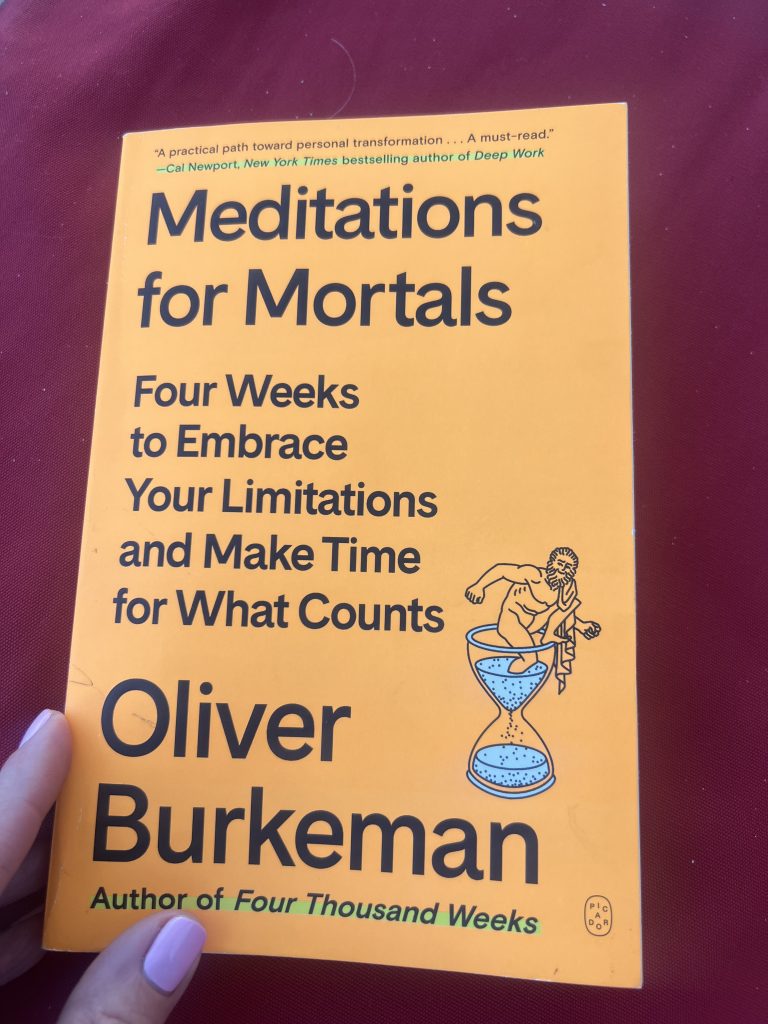

From Meditations for Mortals, by Oliver Burkeman…

What’s an interruption, anyway?

On the importance of staying distractible

“The great thing, if one can, is to stop regarding all the unpleasant things as interruptions to one’s ‘own,’ or ‘real’ life. The truth is of course that what one calls the interruptions are precisely one’s real life – the life God is sending one day by day.”

-C.S. Lewis

…[Y]ou can fall into the trap of… interpreting all the things you’re actually doing with your days as one extended series of interruptions or distractions from what you think you’re meant to be doing with them.

…Next time you do get a moment to hear yourself think… you could use it to ponder the strange assumption of omniscience baked into the notion of minimizing ‘interruptions’ and blocking out ‘distractions.’ The idea that these labels can confidently be applied to things before they happen implies that you always know, in advance, the best way for any portion of your time to unfold – and that should reality beg to differ, it must always be reality that’s wrong. And yet, objectively, all that’s occurring in the world is that certain things happen, then other things happen, then still more things happen. When we define some of these things as interruptions of, or distractions from, other ones, we’re adding a mental overlay to the situation, sorting events into hard categories of those which ought and ought not to happen. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with that; it’s fine to have strong preferences for how you’d like your day to unfold. But at the very least, it’s a reminder not to cling so confidently to those preferences that you turn life into a constant struggle against events you’ve decided, futilely, shouldn’t be happening. Or that you close off the possibility that what looks like an interruption might in fact prove a welcome development.

As the Zen teacher John Tarrant explains, the way we talk about distraction implies something equally unhelpful: a model of the human mind according to which its default state is one of stability, steadiness, and single-pointed focus. ‘Telling myself I’m distracted,’ he writes, ‘is a way of yanking on the leash and struggling to get back to equilibrium.’ But the truth is that fixity of attention isn’t our baseline. The natural state of the mind is often for it to bounce around, usually remaining only loosely focused and receptive to new stimuli, the state sometimes known as ‘open awareness,’ which neuroscientific research has shown is associated with incubating creativity. There are sound evolutionary reasons why this should be the case: the prehistoric human who could choose to fix her attention firmly on one thing, and leave it there for hours on end, so that nothing could disturb her, would soon have been devoured by a saber-toothed tiger. Monks in some traditions spend years developing single-pointed focus, in monasteries expressly designed to provide the required seclusion, precisely because it doesn’t come naturally.

….Looking at things from this angle, you might even argue that what makes modern digital distraction so pernicious isn’t the way it disrupts attention, but the fact that it holds it, with content algorithmically engineered to compel people for hours, thereby rendering them less available for the serendipitous and fruitful kind of distraction.

…We try so hard to cling to the rock face of fixed focus; we fall off, again and again – yet when we do, as Tarrant beautifully puts it, ‘the world catches us every time.’ We lose our grip on our plans for the day, and find ourselves tumbling into life.

***

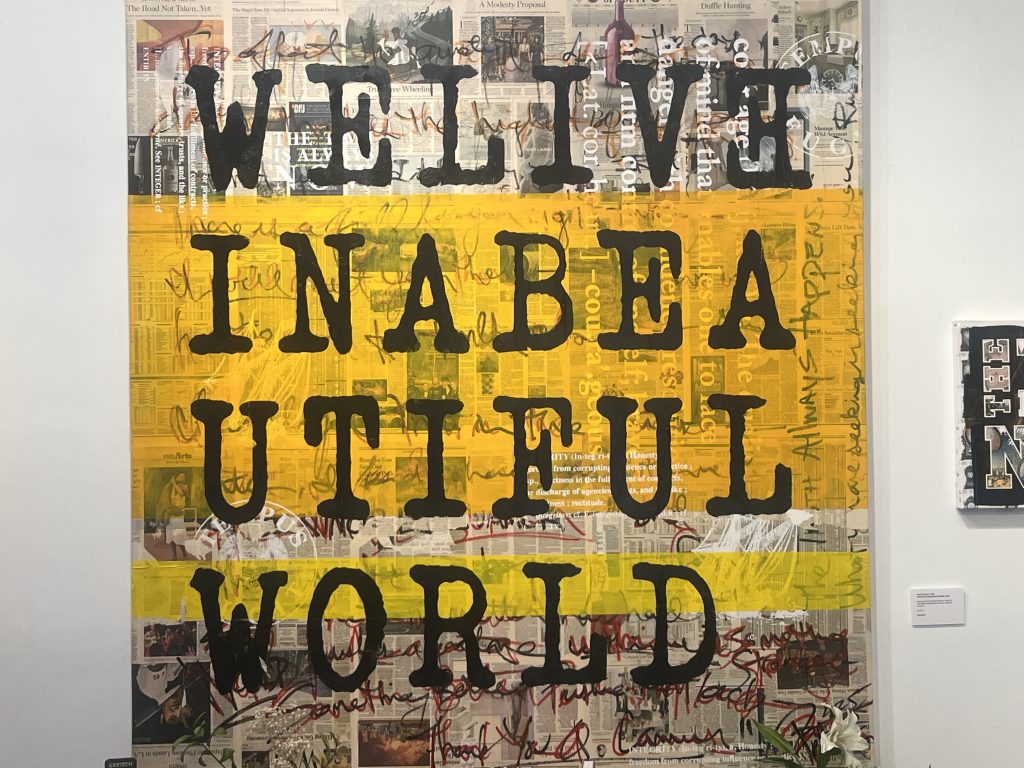

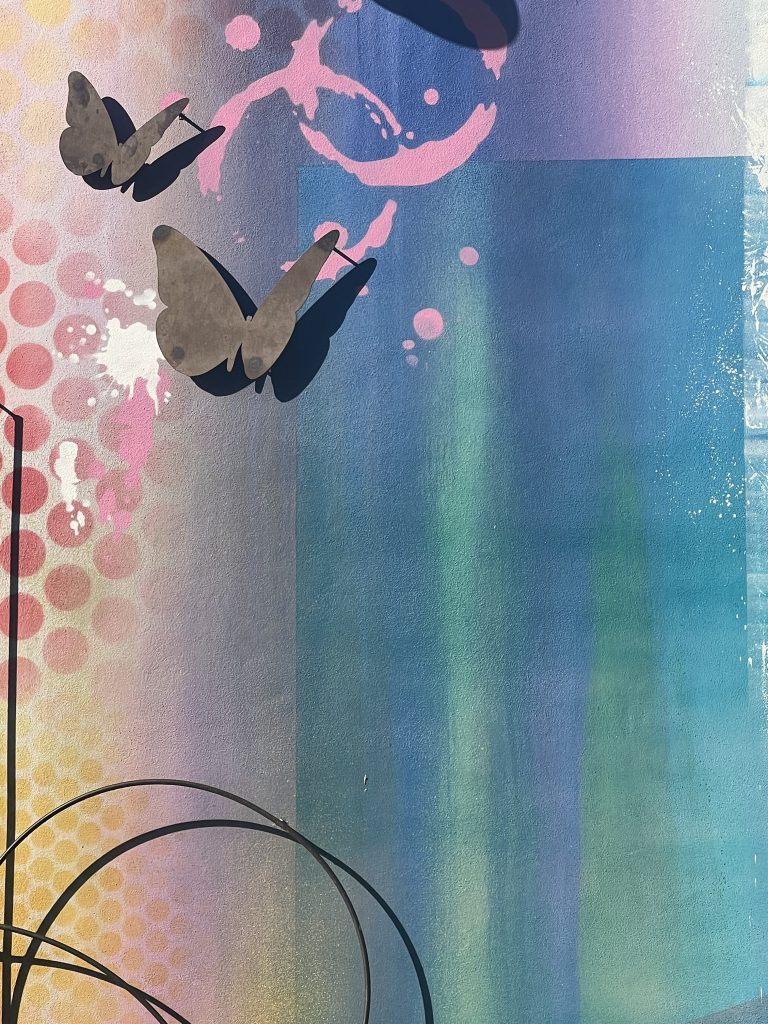

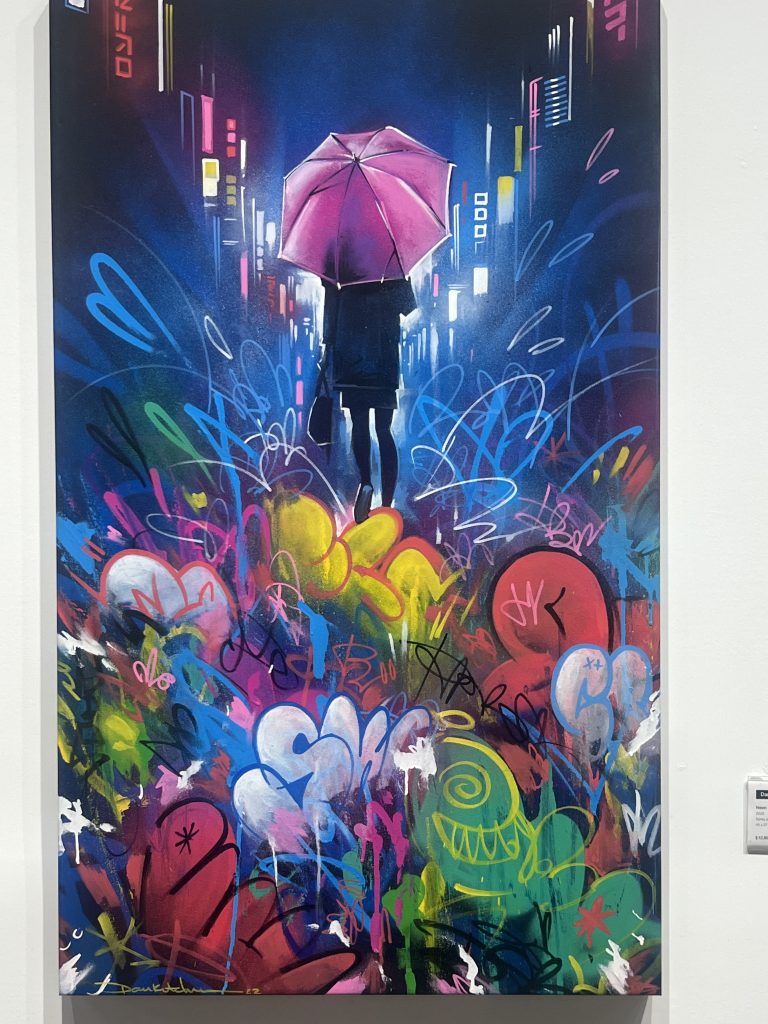

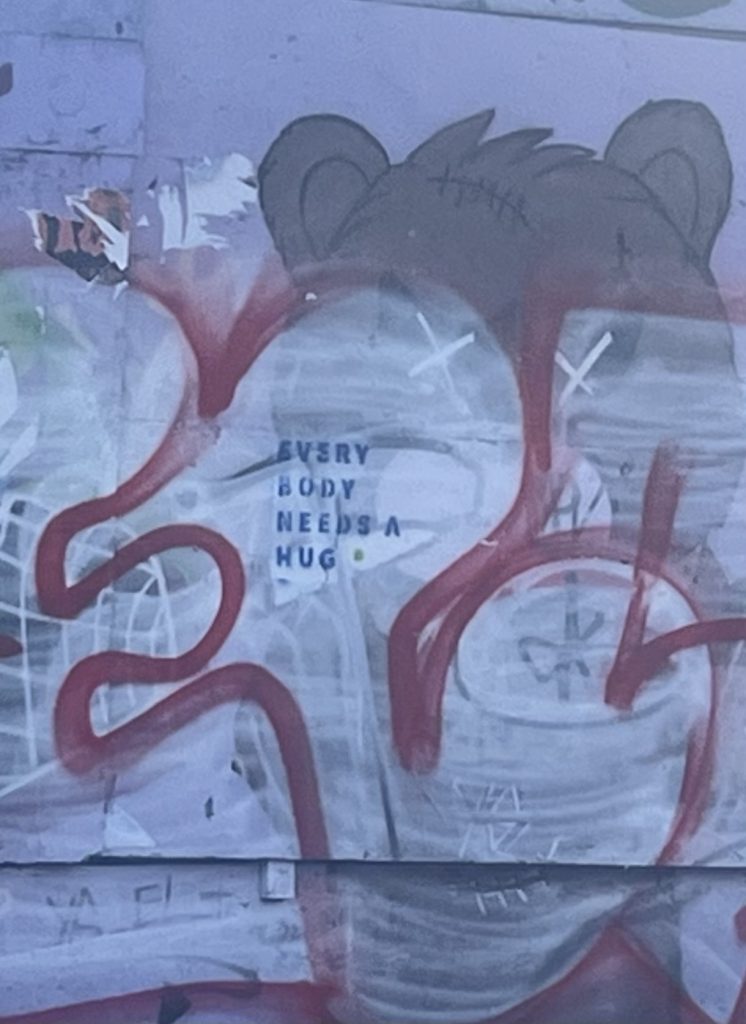

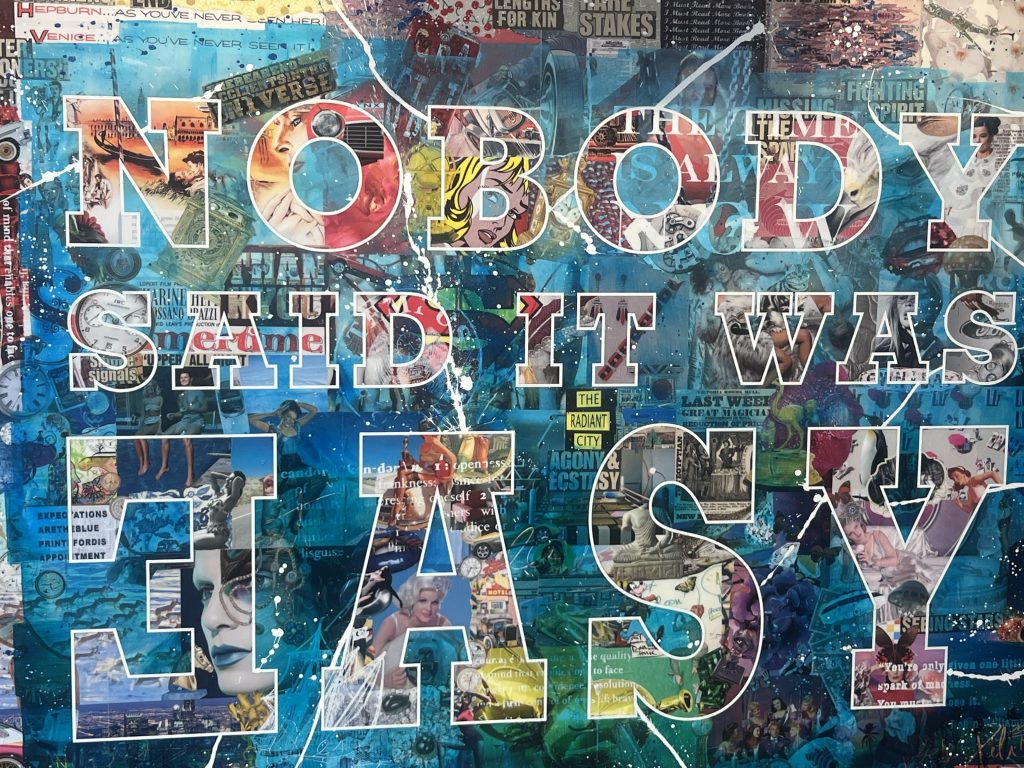

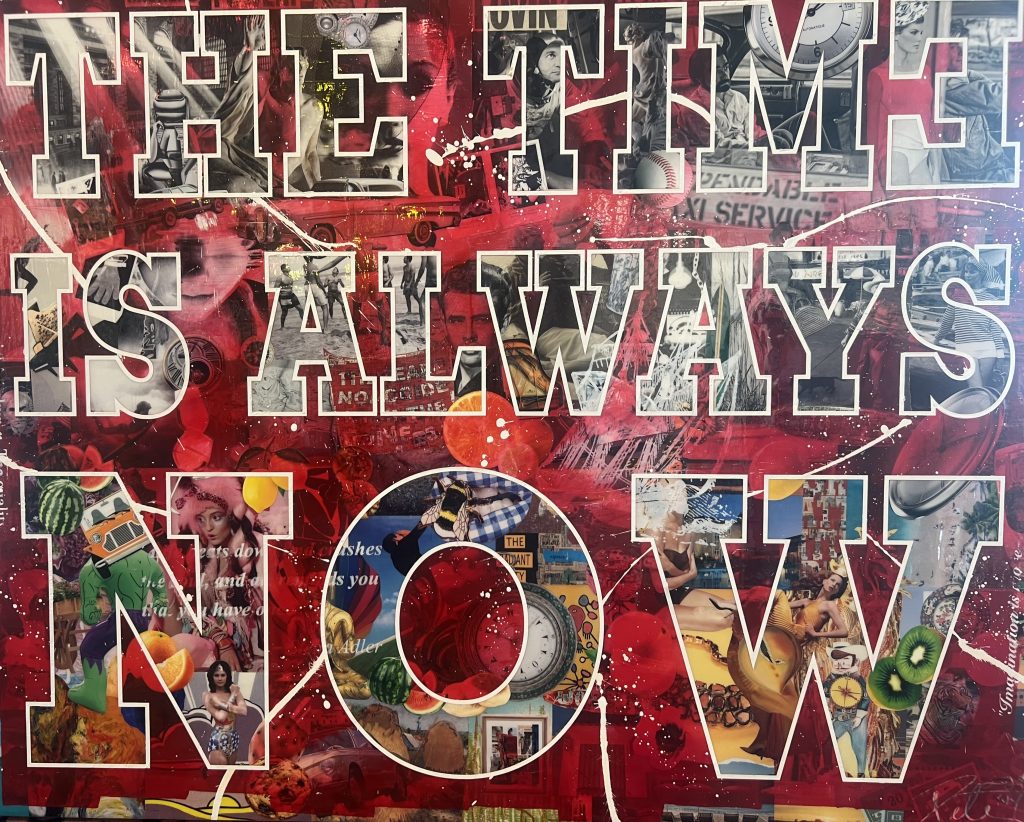

Interruptions courtesy of Nader Sculpture Park and Wyndham Walls (and local sidewalks) in Miami.

My favorite line–“the strange assumption of omniscience.” Thanks Jennifer for this great reminder to live as fully as one can throughout each day, no matter the circumstances. Hope you are safe–with abiding heat to keep you warm in the freeze that is on the way. Peace, LaMon

Good Morning from California and thank you for your lovely inspiring message, Jennifer, my first read of the day.

As always, I feel a surge of excitement when I see that you have posted. Your perspectives and recommended books have helped and comforted me in so many ways. Today’s was especially helpful and provocative in regard to my thinking, very interesting. The photos were terrific!

I have been reading “The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows”, a wonderful book.

The definition “Ozurie” really drew me in with its story … choice, as mentioned in your writing today.

Thank you, thank you and stay safe.