It worries me – dear Bacon friends – when you despair for our country. I’ve had conversations with several of you lately. Lend me your ears, if you will, for a moment! It’s a great day to be inspired by Joseph Tartakovsky, author of The Lives of the Constitution: Ten Exceptional Minds that Shaped America’s Supreme Law.

Tartakovsky’s recent essay in The Wall Street Journal is a beautiful reminder of how much we have to be proud of – to hope for – and to work for. I’ll begin by quoting from that piece. It led me to his book, which I’m dropping everything for right now.

From The Wall Street Journal, Tuesday, July 3d:

Since 1789 the average life span of national constitutions world-wide has been 19 years, according to scholars at the University of Chicago. Meanwhile, “We the People of the United States” are now well into the third century under our Constitution. We’ve lived under the same written charter longer than any people on earth. We’ve had regular federal elections every two years, uninterrupted even by the Civil War.

Yet America’s Founders had serious doubts about the durability of their “experiment.” Alexander Hamilton, in an 1802 letter to Gouverneur Morris, wondered why he had wasted his best years defending our “frail and worthless” charter. In 1832 Chief Justice John Marshall, near the end of his 34-year tenure, lamented in private correspondence that “our Constitution cannot last.”

You might think America’s track record in the subsequent 200 years would inspire greater confidence. Yet many people today feel, as they have after many fraught elections, that the president is either a savior or the harbinger of doom. So it’s worth reflecting on why the Constitution has endured.

There is, first, its text: It is rigid enough to restrain excesses, yet flexible enough to accommodate innovations. It is so terse that you could fold it into a paper airplane (though the guards at the National Archives would prefer you didn’t). It presumes that both governors and the governed will act mostly responsibly. But as Robert H. Jackson, a future Supreme Court justice, explained in 1937: “Checks and balances work as effectively on spite, jealousy or personal ambition as they do on patriotism or principle.”

The Framers also created the world’s first constitution to institutionalize the principle of human equality. Consider that it was an immigrant who put the words “We the People” into the Constitution. He was James Wilson, the brilliant but forgotten Scottish-born founder who taught that under monarchy, in the “attempt to make one person more than man, millions must be made less.”

Popular rule had become more than a slogan. Alexis de Tocqueville visited in 1831 from France, where the crowned heads at Versailles dared not mingle with their people. He was astonished to meet state governors who had kept their day jobs as farmers. Later Tocqueville visited Andrew Jackson in the White House, where the president himself, with no servant in sight, served glasses of Madeira.

America’s progress in respecting the real implications of equality has at times been slow, even glacial, especially with regard to race. As early as 1876, black fathers in Kansas sought to have their children admitted to schools on equal terms with white children. Yet Brown v. Board of Education would not come for another 78 years. The truth that justice will be forever approximated but never achieved is reflected in the paradoxical words of the Constitution’s preamble: the aim of forming a “more perfect” union.

That impossibly shrewd phrase suggests that Americans have a miraculous thing that we must nevertheless strive to make better. In the 1940s, we interned Japanese-Americans out of misbegotten wartime racial hysteria. But we also apologized for it in a 1998 law that was co-sponsored by then-Rep. Norman Mineta. As a child, Mr. Mineta had been taken to an internment camp in Wyoming. He went on to serve 20 years in the House and five years as secretary of transportation…

Constitutionalism is not a mere institutional form but a culture—a set of sentiments, habits and assumptions, a permeating spirit that animates an otherwise lifeless paper scheme. Without this instinctive loyalty, the Constitution’s checks and balances are barricades of foam and counterweights of butterfly’s breath. It is not in having a constitution that our strength lies, but in cherishing it. So long as we keep the faith, our Constitution will be displaced no sooner than an ant tips over the Statue of Liberty.

I wish I could include the whole article! Email me if you want my copy (or subscribe to the WSJ)..

* * *

Enter Tartakovsky’s book:

From David Lat’s recent article in Above the Law:

The Constitution is, you could say, “having a moment.” Thanks to our controversial president, clauses and concepts that don’t get much love — like impeachment, the pardon power, and the Emoluments Clause — are suddenly in the public spotlight.

In Constitutional Law courses, the story of our founding document often unfolds through cases, from Marbury to Brown to Obergefell. But we must remember that it’s also the story of people — We the People, who brought the Constitution into being and who live under its principles.

So if you want to intelligently discuss the latest constitutional issues triggered by the current administration, then you need to understand the people behind the provisions — which is where a notable new book, The Lives of the Constitution by Joseph Tartakovsky, comes in. I recently interviewed Tartakovsky… about his work.

DL: Like many of our readers, you started your legal career by clerking for a federal judge and working at a top law firm, but now you spend your days in a very different way. Tell us a bit about your transition from lawyer to author.

JT: Thanks, David. For four years before law school I was a journalist, writing for magazines and newspapers on literature and history, and an editor at the Claremont Review of Books. By the middle of law school I knew that I wanted to see constitutional law in practice. After three great years at Gibson Dunn & Crutcher LLP, in San Francisco, I joined the Nevada Attorney General’s Office, as Deputy Solicitor General. Perfect for me, since no state gives you a better vantage to see federalism and the separation of powers as they look in real life. Nevada is 86% federal land, so collisions with the U.S. authorities are frequent and tense. Meanwhile, over many nights and weekends, I labored away on The Lives of the Constitution. This makes me, unavoidably, an author, but I still see myself as a lawyer, just one with an almost uncontrollable preoccupation with history.

DL: The conceit of The Lives of the Constitution, telling the story of our nation’s founding document through biographies of ten great individuals who influenced its development, is an excellent one. How did you come up with the idea for this book?

Joseph Tartakovsky

JT: I believe that the story of the Constitution is not merely the story of court cases or theories of interpretation. It is the story of human beings; of Americans; of our politics, culture, economics, elections, wars, depressions, struggles, victories. Plutarch, in his history of the Greeks and Romans, proved that the best way to capture a civilization is to pick a number of figures who did exceptional things and then to follow them through their adventures in life. Examining an individual’s life gives you insights that you’d miss if you just read, say, the documents they wrote. For instance, you can’t understand Alexander Hamilton’s constitutional thought without studying his revolutionary war service.

DL: You’ve picked ten important and influential individuals to profile — but given the longevity and significance of the Constitution, you had to leave many out. Can you share with us how you settled upon these ten figures for the book?

JT: I wanted to recount the history of America from founding to present and to introduce readers to unknown stories. I have famous but misunderstood people, like Alexis de Tocqueville and Woodrow Wilson, and largely forgotten folks like James Bryce and Robert Jackson. Above all I went for people who said striking things that teach us something enduring about our constitutional history.

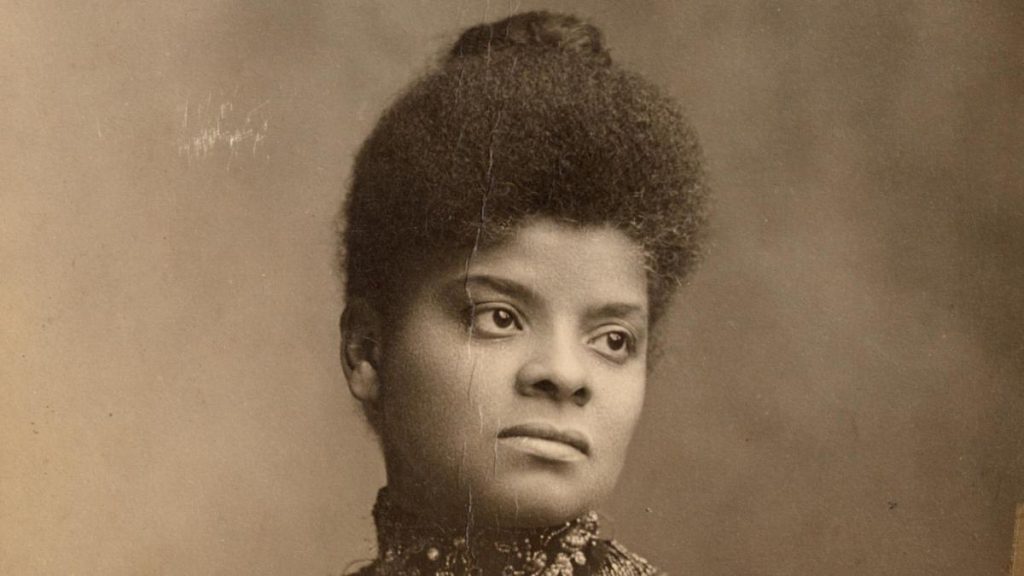

For instance, I first heard of Ida Wells-Barnett, an ex-slave who became our leading anti-lynching crusader in the 1890s, when I read her remark that all black families ought to have a Winchester rifle in a “place of honor” in their home. There’s a lot of constitutional history packed into that statement. I have a chapter on James Wilson, the most important framer no one has heard of, who produced a volume on our Constitution that is as good as the Federalist. And Justice Stephen Field, a Gold Rush lawyer appointed by Lincoln, made arguments about the right to work and regulation that failed to carry the day but that, a century after his death, are now being adopted by courts.

For more of David’s terrific interview with JT, click here.

* * *

From an interview at Joseph Tartakovsky’s website:

Q: What’s the biggest misconception about the Constitution?

A: That faithfulness to the Constitution is simply a matter of ventriloquizing the forefathers. Would it were possible. We rightly revere the Founding Fathers, a glorious generation whose genius did more than any other in history to teach humanity about free government. But as James Madison said, “doubt and difficulties” in interpreting the Constitution would inevitably arise. To say the least. Once the Constitution took effect in 1788, the Founders fell out bitterly on question after constitutional question: the President’s power over foreign policy, the legality of the federal bank, the scope of free speech and the Commerce Clause, and so on. To me, far more illuminating than the founders’ agreements were their disagreements. We honor the men of 1787 most faithfully by trying not to speak in their name but rather to engage in the far harder task of trying to be Americans of their kind—to approach constitutional dilemmas with their intelligence, learning, and patriotism.

Q: You write about some famous figures, like Alexander Hamilton and Woodrow Wilson. Why cover this territory?

A: Alexander Hamilton and Woodrow Wilson provide timeless constitutional lessons. And both are misunderstood. Hamilton has always played second fiddle to Thomas Jefferson. Yet it was Hamilton’s vision of the Constitution, not Jefferson’s, that prevailed. Hamilton gave us the interpretation of a Constitution of breadth, power, flexibility, fit for a nation destined to overmaster the world. The boasts of every State of the Union speech, from our imposing, far-flung military to the President’s stewardship over the economy, were Hamilton’s dream, and Jefferson’s nightmare. Yet Jefferson has a marble temple erected to him in D.C. and Hamilton just barely kept his place on the $10 note. Even with the musical, plainly, his reputation is still not secure.

Woodrow Wilson gets the opposite treatment. Here is a president who has been out of office for 100 years and yet is blamed for everything from undermining the Constitution’s separation of powers to masterminding the present administrative state. Right or wrong, Wilson is fascinating as a president who also spent 25 years as a constitutional scholar and historian. In particular, few Americans ever spoke so eloquently about the question of how to adapt the Constitution to the predicaments of later ages. “The Constitution was not made to fit us like a straightjacket,” he said. “There were blank pages in it, into which could be written passages that would suit the exigencies of the day.” That’s a view of the Constitution that Americans will always wrestle with, even those who disagree.

Q: What is important about Ida Wells-Barnett?

A: Ida Wells-Barnett was a black woman born a slave in Mississippi in 1862 who, by the 1890s, was undisputed as the greatest journalist-crusader in American history against lynching. She helped awaken the nation’s conscience to brutality and sadism of the South’s treatment of its black citizens. Her efforts began (but hardly ended) the march toward actually enforcing the Constitution in favor of penniless and terrorized blacks. Wells-Barnett was also a suffragist. The saga of women’s rights from Seneca Falls in 1848 to the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 is the richest illustration of how profound constitutional change is instigated by ordinary Americans. I find people like Wells-Barnett, or her friend Susan B. Anthony, something like unacknowledged founders. Anthony, for instance, died years before Americans ratified the Nineteenth Amendment. But it makes no sense to describe her as anything but a framer of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Q: This book covers our whole history, but it’s only 220 pages. Why so short?

A: Doing the research needed to write a work of history and law renewed my appreciation for brevity in books. My goal was to write something instructive, entertaining, and short. We’re all busy. Most nights, before turning to my book, I read to my little girls at bedtime. Toddler books are usually about 12 pages. One even had 12 words. They served as models.

Q: What advice do your figures have for Americans today?

A: First, the best antidote to hysteria is a good dose of history. The Constitution has been pronounced dead more or less constantly since the beginning of the republic. Yet the truth is that in earlier eras our predecessors suffered worse strains and faced deadlier enemies. The past gives us a sense of proportion and a chance to avoid repeating our worst mistakes. Second, self-government gives us more than any other form of government, but it also requires more of us, too. James Wilson, a figure in my book—and the most important founder you never heard of—taught that we had a duty to cherish the Constitution, if we wanted it to last. “There is not in the whole science of politics a more solid or a more important maxim than this,” he said, “that of all governments, those are the best, which, by the natural effect of their constitutions, are frequently renewed or drawn back to their first principles.”

* * *

Happy 4th, Bacon friends!!

* * *

Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears! Love you Mary Jo Shankle and Dara Russell, recent co-chairs of Frist Gala.

* * *

Top image credit here.

Last image credit here.

Fantastic interview.

So glad you enjoyed it, dear Betsy! xoxo

Thank you Jennifer! You give me hope AND you recommend a great book. He had me only 220 pages. Happy 4th to you and may the Constituition Be With You.

He had me at 220 pages too!! And May the Constitution Be With You!! (haha – love that, L!!) xoxo

Excellent! With citizens like you, I will always have hope. ❤️

Right back at you, dear Amanda!! xoxo

Long may she reign! Thanks for the inspirational July 4th reading!

Yes Long May She Reign! Well said, Keltie!! So glad you enjoyed this. xoxo

What a beautiful message on this wonderful day of celebrating our nation!

And lots of love to you sweet friend

xoxo Dara!!

Jennifer, betterthangreat post!! I heartedly agree that “the best antidote to hysteria is a good dose of history”…so very true. #persepctive. And thanks for the FG shout-out! xo

Jennifer, betterthangreat post!! I heartily agree that “the best antidote to hysteria is a good dose of history”…so very true. #persepctive. And thanks for the FG shout-out! xo

I took a day of independence from social media yesterday, but catching up on this article today. Thank you, Jennifer, for being on it as usual with this positive and inspiring message. #wethepeople