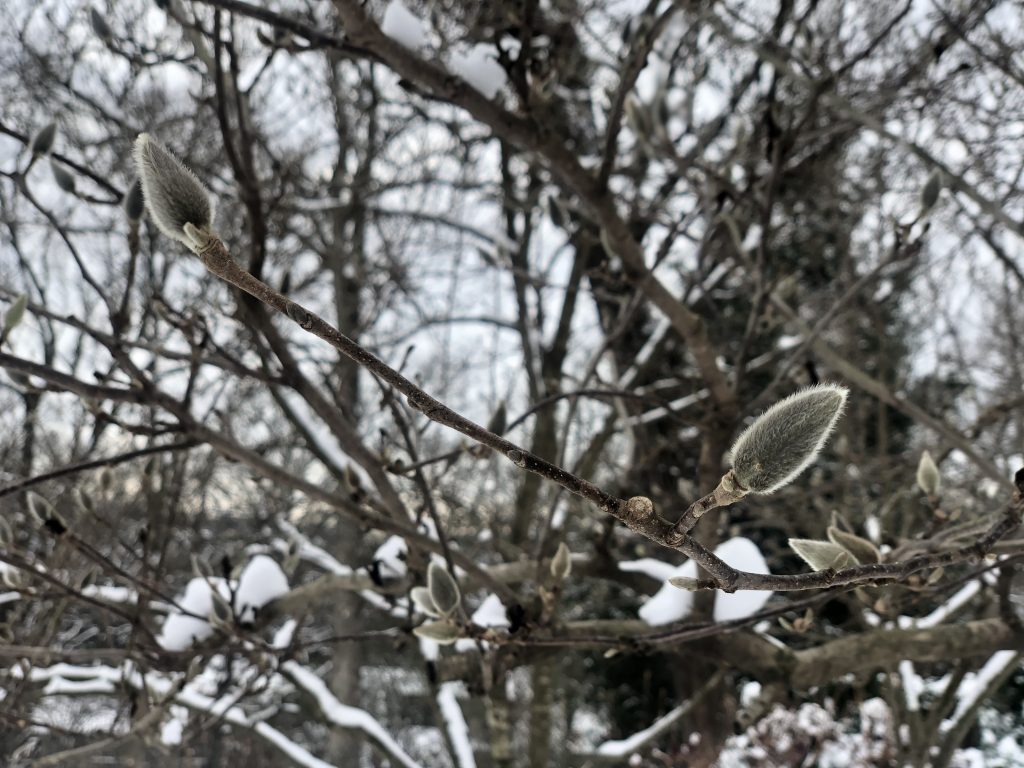

In the hush and glory of this week’s snow, I worry about the boxwoods. Their burdened boughs bend to extremes. De-formed, the bushes no longer resemble themselves. Wretched and wrecked, they need some relief, and soon.

And yet – each moment, each hour – they bear this extraordinary weight.

They bend as they wait for sun and for rain.

The green boughs of the boxwoods hold.

* * *

Today I’d love to share with you a few passages from one of the best books on Christianity I’ve ever read – Unapologetic, by Francis Spufford. I learned about this book after reading Spufford’s enchanting new novel, Light Perpetual (see Bacon review). Here’s the full title – Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity Can Still Make Surprising Emotional Sense.

Unapologetic is a chatty, conversational, witty, feeling-based explanation of Christianity. Sometimes it reads like Madeline L’Engle in A Wrinkle in Time – fantastical wonder and awe – and sometimes like C.S. Lewis, grounded in the hardest of human emotions.

Spufford is an Englishman, which also lends it that special Across-the-Pond flavor. He begins the book by describing a famous bus in London known as “the atheist bus.”

“There’s probably no God,” it proclaims. “Now stop worrying and enjoy your life.”

Spufford responds:

Enjoyment is lovely. Enjoyment is great. The more enjoyment the better. But enjoyment is one emotion… Only sometimes, when you’re being lucky, will you stand in a relationship to what’s happening to you where you’ll gaze at it with warm, approving satisfaction. The rest of the time, you’ll be busy feeling hope, boredom, curiosity, anxiety, irritation, fear, joy, bewilderment, hate, tenderness, despair, relief, exhaustion and the rest… To say that life is to be enjoyed (just enjoyed) is like saying that mountains should only have summits, or that all colors should be purple, or that all plays should be by Shakespeare. This really is a bizarre category error.

But not necessarily an innocent one. Not necessarily a piece of fluffy pretending that does no harm.

…[S]uppose, as the atheist bus goes by, that you are the fifty-something woman with the Tesco bags, trudging home to find out whether your dementing lover has smeared the walls of the flat with her own shit again… Or suppose you’re that boy in the wheelchair, the one with the spamming corkscrew limbs and the funny-looking head… Or suppose you’re that skanky-looking woman in the doorway, the one with the rat’s nest of dreadlocks. Two days ago you skedaddled from rehab. The first couple of hits were great: your tolerance had gone right down, over two weeks of abstinence and square meals, and the rush of bliss was the way it used to be when you began. But now you’re back in the grind, and the news is trickling through you that you’ve fucked up big time. Always before you’ve had this story you tell yourself about getting clean, but now you see it isn’t true, now you know you haven’t the strength. Social services will be keeping your little boy. And in about half an hour you’ll be giving someone a blow job for a fiver behind the bus station….

So when the atheist bus comes by, and tells you that there’s probably no God so you should stop worrying and enjoy your life, the slogan is not just bitterly inappropriate in mood… What the atheist bus says is: there’s no help coming.

Spufford goes on to describe what Christianity offers instead, in his estimation.

It offers a deep consolation that meets the needs of the human condition – something far richer than the atheist bus or, for instance, the “teased and coiffed nylon monument that is “Imagine”: surely the My Little Pony of philosophical statements”. (He has a great sense of humor! This book had me smiling throughout).

“A consolation you could believe in,” Spufford writes, “would be one that didn’t have to be kept apart from awkward areas of reality. One that didn’t depend on some more or less tacky fantasy about ourselves, and therefore one that wasn’t in danger of popping like a soap bubble upon contact with the ordinary truths about us, whatever they turned out to be, good and bad and indifferent. A consolation you could trust would be one that acknowledged the difficult stuff rather than being in flight from it, and then found you grounds for hope in spite of it, or even because of it, with your fingers firmly out of your ears, and all the sounds of the complicated world rushing in, undenied.”

He describes the project of the book as follows:

“No tricks, no traps, ladies and gentlemen; no misdirection and no cheap rhetoric. You can easily look up what Christians believe in. You can read any number of defenses of Christian ideas. This, however, is a defense of Christian emotions – of their intelligibility, of their grown-up dignity. The book is called Unapologetic because it isn’t giving an “apologia,” the technical term for a defense of the ideas.

And also because I’m not sorry.

* * *

I’m laughing! He’s for real, never disrespecting anyone else’s beliefs (well, okay, mostly not disrespecting), and offering a robust description of his own. (“Oh yes: the swearing. Why do I swear so much in what you are about to read? To make a tonal point: to suggest that religious sensibilities are not made of glass, do not need to hide themselves nervously from a whole dimension of human experience. To express a serious and appropriate judgment on human destructiveness, in the natural language of that destructiveness. But most of all, in order to help me nerve myself up for the foolishness, in my own setting, of what I am doing. To relieve my feelings as I inflict on myself an undignified self-ejection from the protections of irony. I am an Englishman writing about religion. Naturally I’m fucking embarrassed.”)

* * *

The green boughs of the boxwood hold, and perhaps, are held.

In Spufford’s words, in another context entirely, there is “ something about the void – which will hold you up, but only if you tip yourself madly forward onto it and ask it to take your weight.”

*

Beautiful!!!

Thank you, Mary!! Xoxo

Thank you, Jennifer.

Thank you for being in touch, Allison… xoxo

Jennifer, this is a perfect start to a Sunday! And I too was worried about the boxwoods, I he bees and the cypress trees. Spufford sounds delightful and reminds me of John Henry Newman’s Apologia. I can’t wait to dig in!

I think you will love it, Lawrence! Let’s talk about it once you’ve read it! Xoxo

Again, I so enjoy your writing. I am a little confused by the idea of “Christian emotions”. Humans can have the same range of emotions no matter their religious or non-religious standing. What makes an emotion specifically Christian? I assume it must be an emotional response to either a Christian belief or Christian experience. I plan to start back writing my blog this month. Of course I still write haiku most days and will include one or two in my blogs. Peace, LaMon

I think you are exactly right about that, LaMon… I think he means the specific feeling in response to an experience perceived to be inspired by God/Christ/the church/some element of the Christian experience. I am eager for you to resume writing your blog! And thank you for your kind words. Xoxo

What a beautiful piece and this book sounds fantastic. I love the idea of “grounds for hope in spite of it” … his writing is charming and so rich, as is yours! Thank you!

Thank you, BK… and yes this book is so fantastic!! Xoxo

Can’t wait to read both of Spufford’s books that you recommend!

Hi Barby! Please let me know what you think!! So nice to hear your voice. Xoxo

My day brightener! Thank you!

I’m so glad! And you’re welcome! Xoxo

Thank you J. Perfect sentiment for today.

I am happy to hear from you Lucy! And so glad it resonated. Xoxo

I cannot wait to binge this book – unapologetically

Haha!! You’ll love it!! Xoxo

Love this, Jennifer. If only you could have seen me traipsing around in the snow late Thursday night, beating the snow from my boxwoods with a broom!

Dearest Dallas ~ I might have given my boxwoods a little bit of help with the broom as well. 🙂 But only after our first snow, not the second one. Sending love!! xoxo

And I just sat back and waited for my boxwoods to hold as I knew they would and promptly bought the book.

Ahhh… your faith. I love that. Xoxo

Such thought-provoking messages. And something to think about: what if there really is no help coming. Yikes. I may have to solve some things on my own. Thanks for making me stop and think and enjoy your photography and commentary.

Whether help is coming or not, it’s maybe a good idea to try to solve them on our own – !? Thank you so much for being in touch. Xoxo