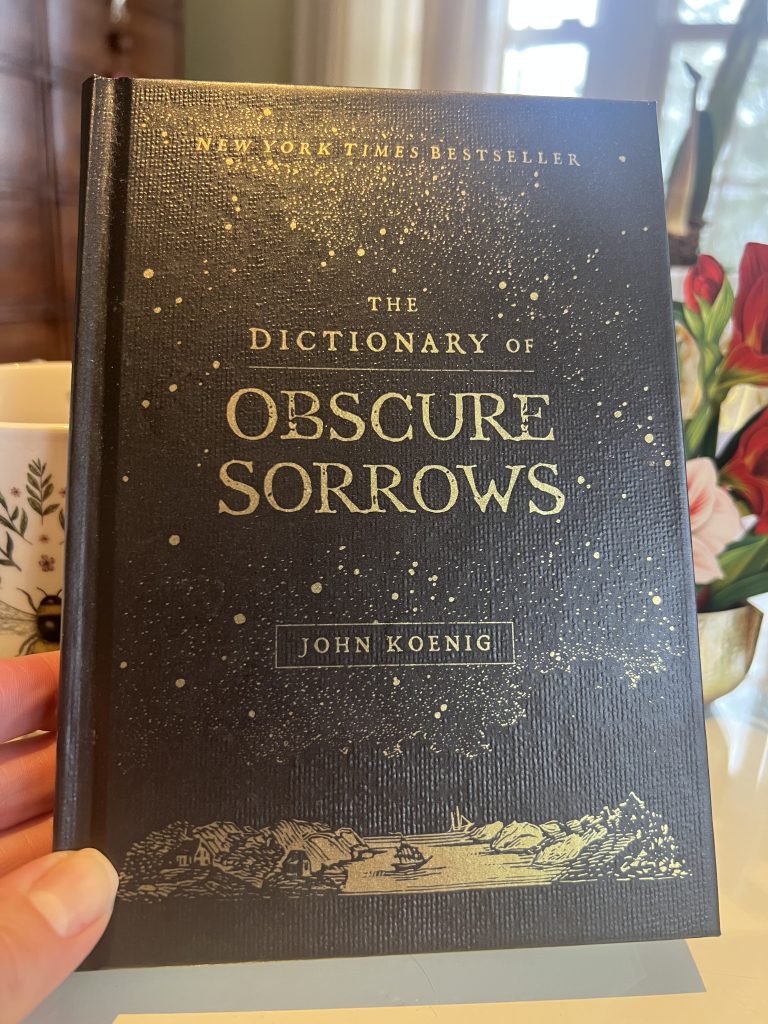

Last week’s foray into German words for post-Christmas feelings made me go hunting for a book I had half-forgotten, The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows. “Its mission,” writes author John Koenig, “is to shine a light on the fundamental strangeness of being a human being – all the aches, demons, vibes, joys, and urges that are humming in the background of everyday life.”

“This is not a book about sadness – at least, not in the modern sense of the word,” he says. “The word sadness originally meant “fullness,” from the same Latin root, satis, that also gave us sated and satisfaction. Not so long ago, to be sad meant you were filled to the brim with some intensity of experience. It wasn’t just a malfunction in the joy machine. It was a state of awareness – setting the focus to infinity and taking it all in, joy and grief all at once. When we speak of sadness these days, most of the time what we really mean is despair, which is literally defined as the absence of hope. But true sadness is actually the opposite, an exuberant upwelling that reminds you how fleeting and mysterious and open-ended life can be. That’s why you’ll find traces of the blues all over this book, but you might find yourself feeling strangely joyful at the end of it. And if you are lucky enough to feel sad, well, savor it while it lasts – if only because it means that you care about something in this world enough to let it under your skin.”

Koenig cobbles together recognizable words, Latin roots, evocative foreign words, and cultural icons in sometimes humorous, sometimes poignant ways.

For instance:

nighthawk

n. a recurring thought that only seems to strike you late at night – an overdue task, a nagging guilt, a looming future – which you sometimes manage to forget for weeks, only to feel it land on your shoulder once again, quietly building a nest.

Nighthawks is a famous painting by Edward Hopper, depicting a lonely corner diner late at night. In logging, a nighthawk is a metal ball that slid up and down a riverboat’s flagpole, to aid pilots in navigation.

midding

n. The tranquil pleasure of being near a gathering but not quite in it – hovering on the perimeter of a campfire, talking quietly outside a party, resting your eyes in the back seat of a car listening to friends chatting up front – feeling blissfully invisible yet still fully included, safe in the knowledge that everyone is together and everyone is okay, with all the thrill of being there without the burden of having to be.

Middle English midding, alternative spelling of midden, a refuse heap that sits near a dwelling. Pronounced “mid-ing.”

redesis

n. A feeling of queasiness while offering someone advice, knowing they might well face a totally different set of constraints and capabilities, any of which might propel them to a wildly different outcome – which makes you wonder if all your hard-earned wisdom is fundamentally nontransferable, like handing someone a gift card in your name that probably expired years ago.

Middle English rede, advice + pedesis, the random motion of particles. Pronounced “ruh-dee-sis.”

falesia

n. the disquieting awareness that someone’s importance to you and your importance to them may not necessarily match – that your best friend might only think of you as a buddy, that someone you barely know might consider you a mentor, that someone you love unconditionally might have one or two conditions.

Portuguese falesia, cliff. A cliff is a dizzying meeting point between high ground and low ground. Pronounced “fuh-lee-zhuh.”

***

I’ve been thinking about my mother, who passed away last June. During covid – isolated, caring for my father as he descended into the fog of Alzheimer’s – my mother become ensnared by a man on Facebook who pretended to fall in love with her. She herself was declining mentally. Over a series of many months, she and this person spent an extraordinary amount of time texting. He did get to know her, I think, and she got to know both the person he was pretending to be and – in some way, of course – him. She certainly learned how to send him money. Finally, using extreme measures, my sister and I were able to prevent this man from communicating with her. She was devastated and furious.

She loved him, having first felt that he loved her. Those feelings of love were real, despite their basis in fantasy and deceit. I wonder if there is a word for such a specific flavor of love – a deeply felt and in some measure real love for someone who is deceiving you. I want a word to honor the beauty and even truth of the feeling despite another person’s manipulation. If there is one, I do not know it.

I think sometimes about his malicious manipulation of her. Those words describe his actions but not necessarily his entire state of mind. I wonder if he ever felt something different, as he got to know her over the months. Did he ever feel anything close to compassion or affection for her? Given the volume of their correspondence, I believe he did know her and understand her very well.

My mother’s sorrow when my sister and I prevented her from contacting this person – in a way, her lover – was extreme. Is there a word for causing extreme pain to your parent on purpose when you feel that you must?

Is there any joy in the mystery that she could still feel and yearn for such love?

What is it within us that seeks such connection?

I wonder if he ever thinks of her. I wonder if my mother, in her dementia care facility, ever thought of him – the person she believed him to be, not the person he was. We never spoke of it.

***

The winter jasmine has never bloomed with such abandon and glory. The conditions this January are somehow exactly right.

***

dolorblindness

n. the frustration that you’ll never be able to understand another person’s pain, only ever searching their face for some faint evocation of it, then rifling through your own experiences for some slapdash comparison, wishing you could tell them truthfully, “I know exactly how you feel.”

Latin dolor, pain + colorblindness. Pronounced “doh-ler-blahynd-nis.”

I plan to read and re-read this post. It’s beautiful and poignant (your mom, sister, you). The new words are to be savored. Thank you.

Xoxo

Wow! This is super powerful and resonant! Bravo for the insight and tenderness❤️

Thank you, Farrell – xoxo

This is just beautiful & emotions are so nuanced. These words help to bring this to light. Thank you for sharing ❤️

Xoxo

It was great to run into you and catch up this week! Lovely word origins. I’m so sorry about your mom and glad you could help her untangle from that awful man.

I loved catching up with you this week, Tracy! What a pleasure! I love talking books with you. Xoxo

Thank you for the pronunciation guide…a word is not mine until I can say it, and I want all of these words to be mine!

Xoxo

The words and their origins are fascinating.

Agreed! Xoxo

Loved this post! I just ordered a copy of the book. Thank you!

Please let me know what you think! It is so nice to hear from you, Catherine! Xoxo

This post leaves me satiated with the beauty and joy and pain of being human. It’s lovely. Thank you.

Ahhh Mary I love your choice of words! Xoxo

Amazing. I had a particularly tenacious flock of nighthawks squawking at me last night at 4am. Thank you, Jennifer, for being authentic and vulnerable and for sharing your wonderful “finds.” So helpful.

I think I may need to make friends with my nighthawks… they come so often. Xoxo

This book of sorrows is one of my absolute favorites. So full of originality, truth and “good grief.” You illuminate it anew for me. Thank you! And thank you for sharing your personal story of your mom, for which you have no words, and yet such insight. Beautiful.

Xoxo

Jennifer, this post is so beautiful! I will buy the book and look forward to reading it.

I’ll be so eager to hear what you think, Melinda! Xoxo

Thank you, Jennifer, for this poignant post- rich in nuances and examples of human capacities and deeper understandings. I deeply appreciate that you shared the story of your mother’s experience written with such compassion.

We may never know what other people are going through and how alike we are in our challenges in life.

From your description, “The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows” offers a rich vocabulary to explore.

Happy New Year!

Xoxo

Brillllllliant post. Love this.

Xoxo

‘Sadness’ reflects the Yin and Yang of life. Finding wisdom in sadness is so important.

It takes practice, right? I’m trying. Xoxo

I’m moved by your exploration and joy, and sadly is no tidy ending here. Only tenderness, grief, unanswered questions—and the fact that you are still listening to your mother’s story, even now.

I stumbled across “DoOS” about three years ago, have dog-earred so many pages, and given it to over a half dozen people. I keep several copies on hand for that very reason. I thought for sure I shared it with you and Mary R.! Different words suit my different moods, but among my favorites are Ozurie, Amoransia, Opia, Heartworm, 1202, Midding, … I could go on and on. I hope Koenig comes out with a sequel to which I would submit

Oniropluvia:

The state of dreaming or being sleepy while listening to the soothing sound of rain.

roots…from the Greek oneiros (“dream”) and the Latin pluvia (“rain”).

Thank you for bringing this brilliant book to your audience, Jennifer and for always sharing yourself with us with such authenticity. xo

Oh Mary Jo, I LOVE your word!! Oniropluvia… I’m writing that down on the page opposite the title page of my book! I’m so grateful to be sharing the journey with you. Xoxo

I love word books, word-a-day calendars, and blogs about words. Thanks for the intro to this one. Peace, LaMon (I no longer get you responses to my replys in my inbox. It may be because I am no longer on WordPress.)

I’m not surprised that you are such a lover of words, LaMon! Xoxo

Jennifer — I can hardly wait to buy this book and spend more time with the words and insights you have shared. I can only imagine how frightening it was to discover the relationship your mother had with the man deceiving her and how difficult it was to end a relationship that meant so much to her. My heart aches for you both. So glad you had your sister for support. I don’t what I would have done without my sisters the last years of my mother’s life. Thank you for sharing this beautiful post. Now to order the book.

Dear Ophelia ~ thank you for your kindness and compassion. I also am not sure how I would have managed without my sister as our mother and father declined. We are the lucky ones. I bet you will love this book as much as I did! I always appreciate you being in touch. Xoxo

Extremely beautiful and resonant. I love words, I love emotions and I love the reality of joy and sadness co-existing and sadness being a part of our FULLNESS……really our longing for the new heaven and earth. Thank you.

That is so beautifully said, Missy. Thank you – xoxo

This was a beautiful post. Thank you for sharing that hard story about your mom. Your question: “Is there a word for causing extreme pain to your parent on purpose when you feel that you must?” stopped me in my tracks. As my mom disappears into the long goodbye of dementia, I will want a word for that as well.

I am so very sorry that your mother is on this path, Sara. There is so much sorrow. There is also a great deal of tenderness, I found. In the end, I wouldn’t trade it. I am grateful for the love that grew between us at that time. Xoxo

How can a post about words leave me speechless? This one does. I sometimes fall into a deep river of grief over my own mother, who died in 2023. These words tap into so many conflicting emotions. I’ll be re-reading them again and again. A beautiful, profound post. Thank you, Jennifer.

Your comment means so much to me, Kim. Thank you for being in touch! Xoxo